At the start of 1917, Arthur Zimmerman, the head of Germany’s Foreign Office, sent a secret coded telegram to the German ambassador in Mexico. It had instructions for the ambassador to meet the President of Mexico at once, and convince him to join the Central Forces in the on-going World War. It was a desperate attempt to ensure that the US does not enter the War, and if it does, Mexico should use its convenient location to try and neutralise the US efforts and keep it away from Europe. The offer promised Mexico that it would gain back its lost territories of Texas, Arizona, and New Mexico as spoils of war.

On the other hand, the Allied Forces led by the British and French were keen to have US join them. With the unending trench warfare, a strong ally like the US could help them cast a few damaging blows. Russia was already proving to be weak, both on the domestic front due to a strong threat to the monarchy by the Bolsheviks, and the fizzling out of the Eastern European front of the war with improper supplies and re-enforcements.

With many falling pieces, the British became desperate. They decoded the Zimmerman Telegram and shared it with the US, persuading them to join the war. It, however, did not prove to be forceful.

To save themselves and ensure that the sun does not set on their empire, they made conflicting promises to several parties. All these promises had one end in sight – their own victory. Seeking victory is admirable, but when it is based on promises made to allies, knowing fully well that they cannot be delivered, it is the ugliest form of realpolitik.

First, the British aimed at ending the Ottoman rule over Anatolia. As Turkey joined the Central Forces, defeating it became important to ensure that the Bosporus Strait is controlled to keep up the shipping lines with Russia. But to attack the Ottoman, the much revered Muslim power which ruled for over four centuries with the perception of being the ‘Caliphate of Islam’, would not be an easy task. Muslim nations and people across the world would heavily protest it, making the British a direct attacker of Islam. The fact that the Indian sub-continent saw the Khilafat Movement by Ali Brothers, joining hands with Gandhi proved these fears credible. They gained validation from Gandhi who went on to add the restoration of Hejaz to Muslim rule as one of the demands of the Non-Cooperation Movement of 1919. To damage this Turkish hegemony, a revolt had to be fomented from within.

To this end, the British spotted Hussein ibn Ali, the Sharif of Mecca, and more importantly, a descendant of the Prophet and his Banu Hashim clan. In the year 1916, an elaborate series of ten letters were exchanged by Henry McMahon, the British High Commissioner to Egypt (and the same man famous for his McMahon Line that demarcated India and Tibet – now China). Hussein ibn Ali was encouraged to initiate a rebellion by the tribesmen of Hejaz against the Ottoman monarchy. Called the ‘Great Arab Revolt’, it aimed to push back the Turkish ‘foreign’ rule and replace it with the home-based Arab State. A promise was made to create a unified Arab State from Syria to Yemen. To ensure clarity, Hussein ibn Ali added ‘Palestine’ to this territory, which the British approved, believing it to be simply a re-statement of the obvious. It would take four years for the British to change their stance.

Hussein ibn Ali Al-Hashmi, the Sharif of Mecca, who would eventually be betrayed by the British and defeated by the now-ruling Ibn Saud family which supports Salafi thought, a passive sympathiser of Zionism and Israel.

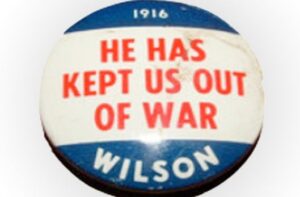

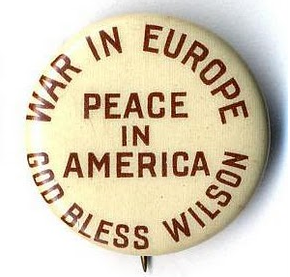

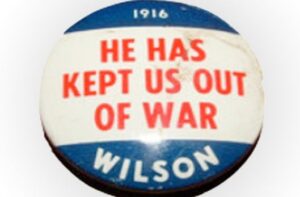

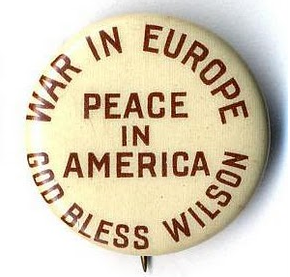

Second, the British would pull all strings required to drag the US into the war. The re-election of Woodrow Wilson as the President in 1916 made this task difficult. In one of the closest Presidential Elections of US, President Wilson managed to defeat his Republican opposition, Charles Hughes. California proved to be a decisive State, which Wilson won by a margin of mere three thousand votes. The entire campaign of Wilson was based on the fact that he kept the US out of the World War, something that looked like a triumph and ensured his election victory.

Badge from the Woodrow Wilson Presidential campaign of 1916.

Another badge which celebrates Wilson keeping US out of war.

However, the British desperation would make them explore, and exploit, the Jewish dream for the promised land. In the 1890s, a man named Theodor Herzl would go on to write a book titled ‘Der Judenstaat’ – The Jewish State. He then would deliver a powerful speech at the First Zionist Congress held in 1897 in Basel. He proposed a clear idea to achieve the Jewish State – a steady and gradual migration of Jews to Palestine. To ensure that Jews aren’t seen as hostile invaders, he recommended that they purchase farm land and houses, and strengthen the population. This, he timelined, to happen for about fifty years. Once a substantial population of Jews is mobilised, he called for an independent sovereign State to be founded – the State of Israel. While it seemed far-fetched at that time, Israel would surely be founded in just about fifty years, in 1948, adopting Herzl as the father of the new nation.

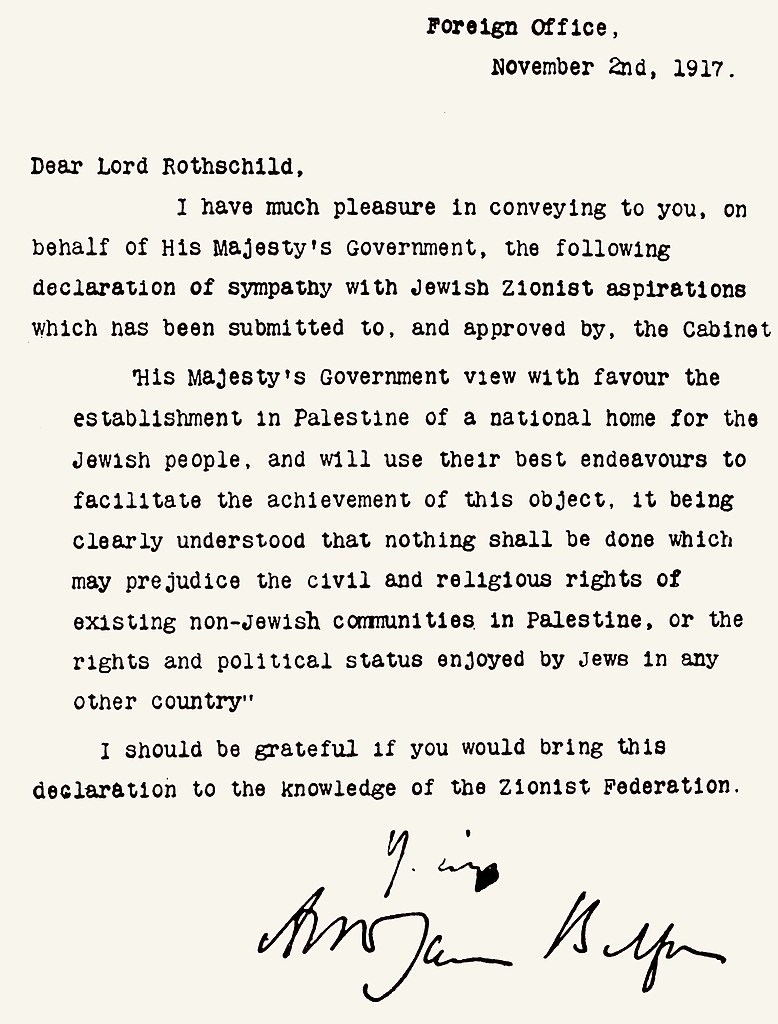

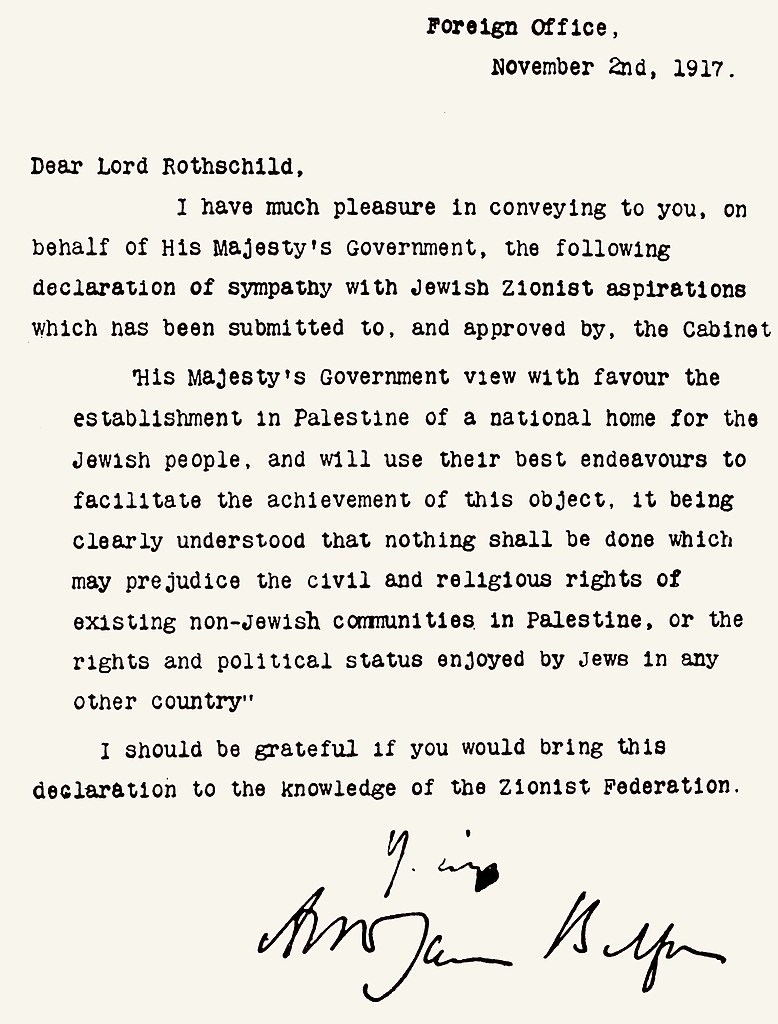

But the Zionist aspirations looked feeble during the World War. Until, of course, the British would use this for their ends. As the Jewish lobby in the US exerted strong influence over the Presidential policies, the British wanted the Jews to lobby for the US to enter the World War. In return, the British would promise – no points for guessing! – the promised land of Palestine. In a letter written by Arthur Balfour, the British Foreign Secretary, to Lord Rothschild, a leader of the British Jews, Palestine was proposed to be made the Jewish State that the Jews aspired to build. This worked, and within a month of President Wilson taking his oath, he declared war on the Central Forces.

Balfour Declaration (1917)

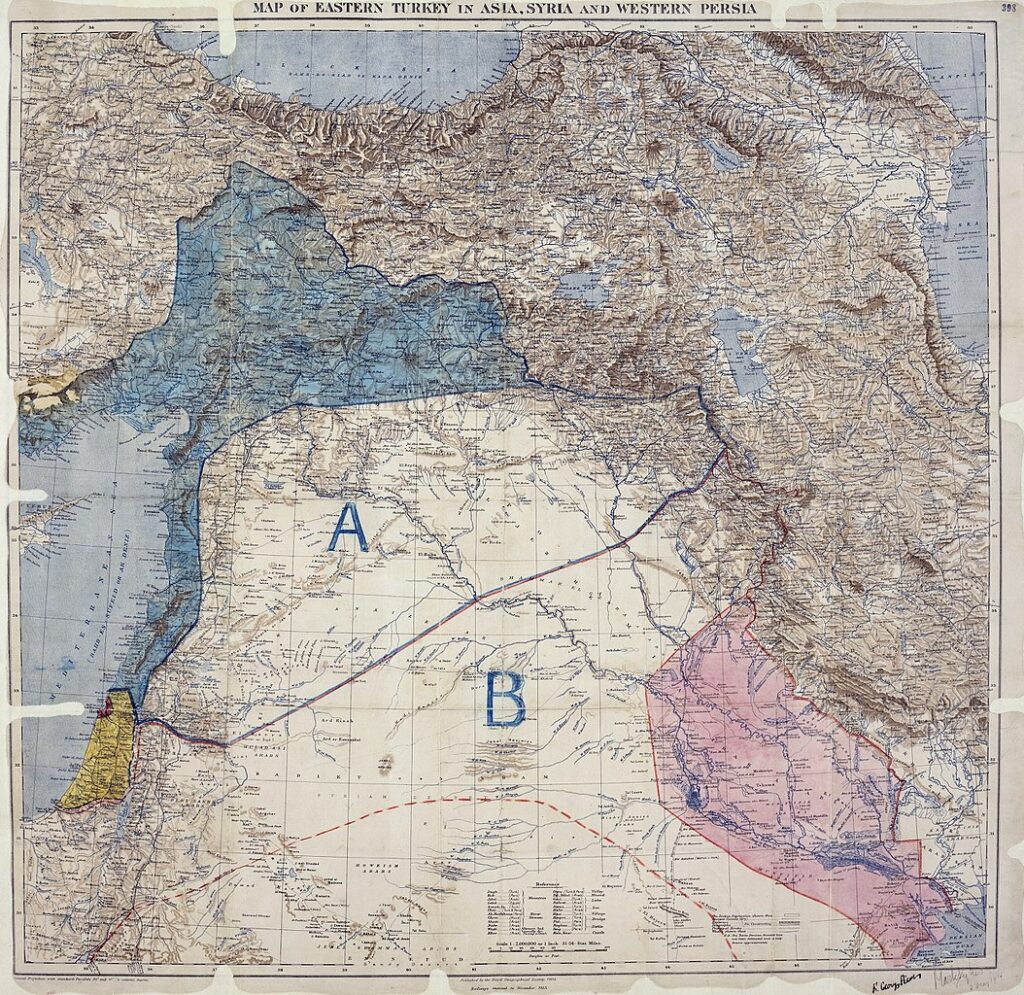

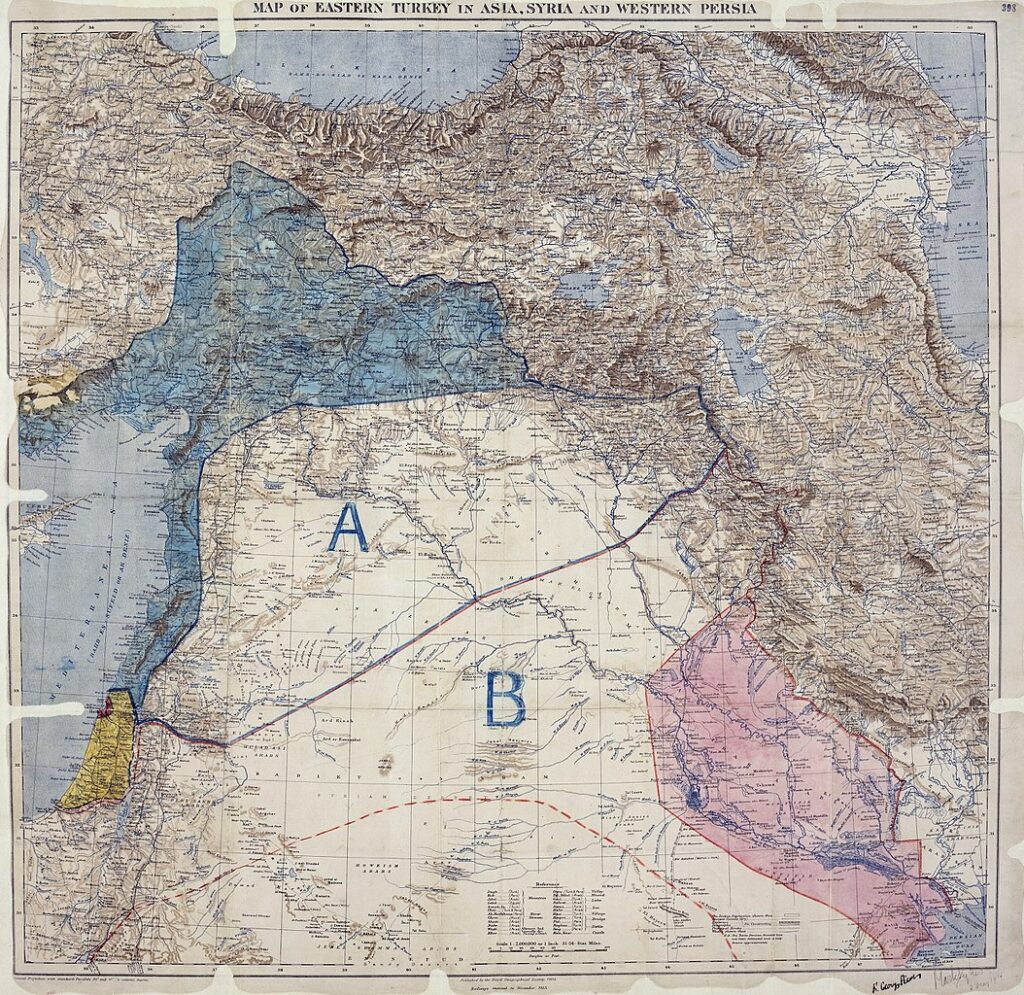

Third, the alliance of Britain, France, and Russia, involved some daydreaming. The Triple Entente, as they were called, would cut out the middle east between Britain and France. The Sykes-Picot Agreement would demarcate areas to be taken up as their own by these two countries. The British promised themselves that they would get Jordan, Southern Iraq, and – I need a drum roll here – Palestine!

The Demarcations by the Sykes-Picot Agreement (1916)

After the war, the British proved true to their own promise to themselves. Until ousted in 1948 by the birth of Israel, they governed Palestine as a Mandate under the League of Nations. Their hearts would change again as they find President Gamal Abdel Nasser of Egypt to be their new enemy as he nationalised the Suez Canal. They then join hands with Israel and invade Egypt, only to be humiliatingly subdued and defeated by Nasser.

The modern history of Palestine is, thus, riddled with conflicting promises. The British slyly withdrew when they could control the territory no more and had a final nail in the coffin as a super-power.

It is this Palestine, the land that was promised not once, but thrice – to the Arabs, the Jews, and the British themselves – that cries under the oppression and the growing settlements of Israel. A land where Moses, Jesus, and Muhammad (may peace be upon them all) walked, now witnesses the flow of blood. And the new Holocaust continues.